In Santa Barbara I told myself that by the time I finished untangling my hair, I would have mentally recovered. I finished untangling my hair by the time I left Redondo Beach, but I have still not mentally recovered.

There is something about what happened on the night of Thursday 5th July that I have yet to fully process.

Catalogue of events:

I rowed 2AM – 5AM in order to round Point Arguello faster

7AM – 2PM was the toughest rowing I have ever done: 25knots NW in the face, carving across waves in order to avoid getting swept south to the Channel Islands.

I told myself that as I passed each oil rig, conditions would get better. They did.

I dug in.

For 7 hours I rowed as hard as I can row.

I celebrated rounding Point Conception by eating the entire 750 kcal packet of Kettle Chips (Organic Salt & Vinegar flavour) I had been saving all trip.

I took a nap.

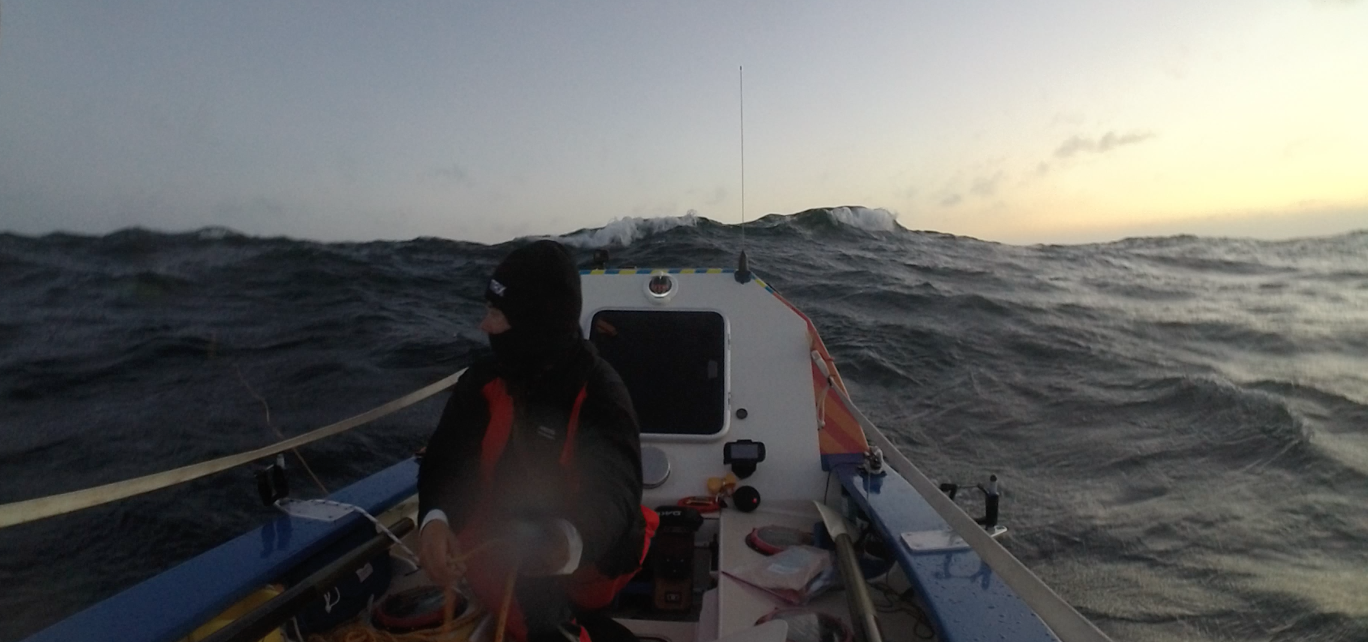

The wind picked up. The swell became 12ft and very steep. I was unsettled by this and by the current that seemed to be prising me away from the coast.

I started to message back and forth with my team about heading for Oxnard rather than Santa Barbara.

Then the W’ly wind died.

The sea became agitated.

There was a warning whiff of air from the land, then an apocalyptic blast came out of nowhere: 35 knots of wind 100 deg F, a phenomena I know from Europe as katabatic winds, known locally as the ‘sundowner’ or ‘Santa Ana winds’. They occur approximately 15 times per year, usually in the autumn/ fall.

2.5 miles upwind of an oil rig, I scrambled to deploy my sea anchor.

Time: 7:30PM

The sea anchor hooked into a current heading westbound that pulled me into steep W’ly swell. The swell was mashing with the new N’ly wind-waves. The boat was being rocked viciously and punching stern-first into waves.

I hear voices, people’s voices and open the hatch to look. There are no people.

I retrieved the sea anchor and tried to row, but it was pitch black and it was like boxing, blind.

The second time, the sea dragged me away from land, towards the westbound shipping lane. Soon I had lost any protection from Point Arguello and the waves began to break. ‘Growlers’ I’ve since learnt they’re called. Breaking waves that roar towards you like an oncoming train. They hit the back of the boat like a car crash. Boat-breaking conditions.

By then it was 4AM.

I took 3, 4, 5 impacts from Growlers, before I told myself, “you have to get out of here. You have to get off sea anchor.”

I have several visuals of the next sequence of events. Opening the hatch to get out and taking a wave on the head and neck, wet hair, the dribble down the back, the wretchedness of that moment. Then I am on deck ready to haul in the sea anchor and I glance right to the forward hatch – a small hand is trying to press the hatch open from the inside.“That’s not real Lia.” I tell myself.

I begin hauling the retrieval line, hand over hand as white water envelops me and I am knocked to my knees. Ouch my left knee.

Waves threaten to wash me overboard, but I crouch low and keep hauling.

My focus and determination in that moment… I am proud of myself for that. I could have cut the sea anchor away as a last resort, but I got the anchor back in and the impact of the Growlers was immediately less.

When Sarah Outen was tumbled in Typhoon Mwar, she struggled for a year with what she later said were “mental health issues.” Ellen McArthur never raced again after her Jules-Verne solo non-stop round the world record win. “I went to a very very dark place.” she told me as we chatted at the back of the fishing trawler heading out into the Rade de Brest at 2AM to witness Francis Joyon break her record in IDEC I. “And I never want to go back there.”

In Santa Barbara I suffered waves of intense fatigue, hunger and battled with a voice inside my head that alternatively wanted to cry or scream. I was neither here nor there, back out in the ocean nor among the holidaymakers celebrating July 4th weekend. I felt adrift. The row on to Redondo Beach helped. The sun kissed my skin, there was space in my head and I began to think that perhaps I had visited the place to which Ellen McArthur never wanted to return and that had for a time, been a challenge for Sarah Outen.

“I can’t continue and yet somehow I do,” I had messaged my friend and doctor Aenor Sawyer, the morning after that harrowing night as I began a 30 mile rowing day to Santa Barbara.

I had gone from amber to red to grey, severe sleep deprivation on top of hours and hours of hard physical exercise. I was beyond empty, I was broken. “I can’t continue.” And yet I had to. I had to row out of the shipping lanes and I had only one day of food remaining.

“Has it put you off?” my brother asked this morning. “Do you still want to row the North Pacific?” asked a friend earlier this week.

This isn’t my first traumatic experience at sea, but I crossed a threshold on this occasion and I need a new tool kit for dealing with the aftermath of those event/s.

That night doesn’t change my resolve.

In many ways I am grateful, in terms of training it doesn’t get more authentic than this.